While touring the UK with X-Ray Spex in the late ’70s, vocalist Poly Styrene had a very close encounter with a UFO. A luminous pink fireball of energy glided up to her hotel room window and gave Poly a message, which she dutifully reported the next morning to her band. “Everyone thought I’d lost the plot,” she told an interviewer. It was “the moment that changed me forever,” she said. Her life would follow an extraordinary, often deeply painful trajectory in the aftermath of that event.

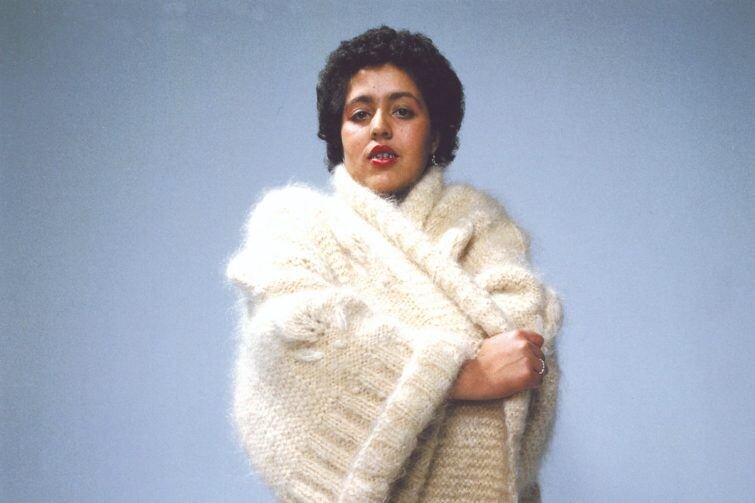

The Sex Pistols and the Clash symbolize the era for most, but X-Ray Spex was one of the very few bands produced in the first wave of UK punk to include a true visionary in its ranks. Marion Elliott was an Anglo-Somali misfit raised by a single mother inside the racial pressure cooker of ’60s-’70s Brixton. In 1976, while still a teenager, she reinvented herself as Poly Styrene, formed X-Ray Spex, and promptly produced a string of hit singles culminating in the classic album Germfree Adolescents in 1978. Besides the blunt intrusion of sax and the affecting yowl of its singer, X-Ray Spex was distinguished by Poly’s penetrating imagination, satirizing the impacts of modern dystopian consumerism in songs like “Identity” and “The Day the World Turned Day-Glo”, and producing the weirdest and best-ever paean to pubescent OCD with the title track of the LP. If the Pistols and others put a cartoonish boot to the establishment, X-Ray Spex demonstrated something closer to the subtle prescience of JG Ballard or William Burroughs. And as a visual property, the intensely charismatic teen was second to none: an ethno-plastic futurist screaming about “Genetic Engineering” through a shocking grid of silver braces. Even inside London’s punk elite, Poly Styrene was more original than most.

“I think my mum was on a completely different level to most of her peers within that scene,” says Celeste Bell, daughter of Poly Styrene, and director (with Paul Sing) and cowriter (with Zoë Howe) of Poly Styrene: I Am a Cliche. “I’m not just saying this because it’s my mum,” she continues, calling Stir from the UK. "I think objectively I could say this, that my mother’s level of artistry was really above and beyond most of her peers at the time. Her level of creativity, and how insightful, how intelligent she was, and just how otherworldly. I think John Lydon actually said in an interview once that he was sort of scared of her. Those are the words that he used.”

Bell was put in charge of her mother’s archives when cancer took Poly Styrene in 2011 at the age of 53. It was five years before she could put their often dramatic relationship behind her and delve into the treasures she left behind. I Am a Cliche is a rich audio-visual memorial to the artist, but it’s also the story of a mother whose extreme bipolar disorder and dedicated spiritual path—she famously joined the Hertfordshire Hare Krishna sect sponsored by George Harrison—took a heavy toll on her child. Aided by old bandmates, collaborators, friends, and relatives, Bell narrates this haunting memoir of tumultuous family life, sparing few details, describing at one point how she turned herself in to social services, in turn triggering a painful custody battle that finally placed Bell in her grandmother’s care.

Equally, this is a deeply loving tribute to a truly extraordinary person, and for Bell a bid to make peace with her experiences. Childhood was difficult, she says, but there’s much to be valued now. “A lot of what she was doing was really ahead of its time. She was very strict on healthy eating, she also didn’t allow me to watch television, she was really aware of the dangers of too much media, and too much advertising. She just really wanted me to be surrounded by books and learning. All of those things she really instilled in me in an early age were very, very helpful in later life. Growing up and spending that time in the Hare Krishna movement, the alternative community, it gave me this foundation that I think very few people have. At the time, when I was a teenager, it was, 'Oh my God, I had the worst childhood, I couldn’t do anything, I couldn’t even watch TV.’ Now I understand it, and I’m really appreciative of that, and if I had kids, I would want to do something similar.”

It’s significant that Poly Styrene would reject so extremely the lures of hyper-modernization. Including an emotionally shattering residency at CBGB in New York City, her brief but potent period as a pop star seemed to manifest the prophetic critiques woven into her lyrics. As her sister Hazel Emmons notes in I Am a Cliche, Poly Styrene had very quickly become a commodity. X-Ray Spex guitarist Paul Dean recounts that, within 24 hours of being told by the day-glo flying saucer to “give up the electric, plastic way of life,” a stricken Poly Styrene was tearing off her clothes in the back of a car and pleading, “I want to go back. I want to be Marion.” What on earth was happening to her? “My mum did have visions,” says Bell. “That was a feature of her illness, because she had a very severe form of bipolar disorder that did manifest as something more akin to schizophrenia. That’s why she was misdiagnosed as schizophrenic, because some of the things that she would experience would be visions, voices, auditory and visual hallucinations.”

Does mental illness provide a fully adequate explanation for Poly Styrene’s uncanny mix of magnetism, inspiration, and clairvoyance, however? Human experience is littered with centuries worth of literature concerning mystical visions and visitations, and both the suffering and the genius that consistently pours from these encounters with the numinous. It’s a tricky subject inside our scientific-materialist paradigm, and certainly not to be taken lightly, but Bell is prepared to entertain the possibility that there’s more to her mother’s story. “I would have been very dismissive of it, especially when I was a teenager,” she says. “But as I’ve gotten older, I feel like my mind has opened a little bit, and yeah, I think if anyone was a natural mystic, it was my mum. Because she was highly intuitive, and she was extremely creative, and she was a very spiritual person with very solid spiritual beliefs, and she did have lots of unexplained experiences and abilities.” In the end, adds Bell, “it’s a much greater philosophical question”.

What remains is the still provocative nature of Poly Styrene’s art; the “pretty accurate predictions,” as Bell puts it, “about where society was heading." She remembers a lot of Freud and Jung on the bookshelf, and her mother’s taste for Ginsberg and the Beats. "She also was just an avid reader of the news, and newspapers, and TV news, and I honestly think she got most of her inspiration from just current affairs. You know people who are really good at the stock market? They’re able to see current trends and make forecasts based on what’s going on, and what’s happened in the past, and that’s something my mum was able to do. But she had another level; a deeper insight than most people into what was really going on behind the scenes.”

It’s true that the best and most durable pop-art simply maps itself onto any period. And it makes sense that the 43-year-old “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!” has emerged on TikTok and elsewhere as a rowdy gateway for teen feminist punks. But it’s tempting and maybe only a little frivolous to point out that Poly Styrene has also mysteriously returned, like a prophecy-bearing UFO, in the same year that an entire planet is talking about identity, genetics, and germ-free everything.

Stir, May 2021